The Leesburg Town Council voted 5-2 Tuesday night to pass a resolution opposing the North-South Corridor and its components, despite firm requests – some have called them threats – from Loudoun Board of Supervisors Chairman Scott K. York and Loudoun Chamber President Tony Howard not to do so.

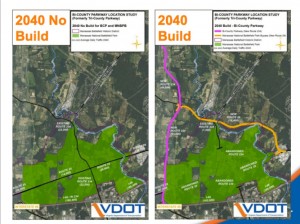

The resolution opposes construction of the Bi-County Parkway (formerly the Tri-County Parkway until shifted west several years back), which is a component related to the North-South Corridor aimed at improving connectivity between Prince William County and Dulles International Airport and the surrounding area. The corridor itself actually refers to an area, not a specific road; however, the construction of the Bi-County Parkway would complete a new direct four-lane path from I-95 in Prince William County to Route 50 in Loudoun. In its entirely, it would link I-95 all the way to Route 7. All segments of that connection are planned for at least four lanes of traffic, with few interchanges and plenty of traffic lights.

The Loudoun Chamber and Board of Supervisors as well as the state have put their support behind project, but a majority of the Leesburg Town Council believes the road would spark denser development in Loudoun’s Transition Policy Area and dump traffic on Route 7 that would overflow onto town streets.

“The problem I have with the North-South corridor is that … as with Prince William County, they’re concerned about protecting the Rural Crescent; in Loudoun we’re concerned about protecting the low-density transition area,” said Mayor Kristen Umstattd.

Umstattd and at least one other councilmember also pointed out that Interstates 95 and 81 were only four lanes in sections.

“I don’t want to see another I-95 or Interstate 81 coming up from 95 and dumping onto Route 7,” Umstattd said.

The Chamber’s Howard called that point “a completely misunderstood representation of what this project is proposed to be.”

Howard said the four-lane road, which would have traffic signal primarily instead of interchanges, would in no way resemble those interstates.

“I’m very disappointed in the vote,” Howard said. “The actions they took yesterday weren’t necessary. It’s not reasonable that Leesburg will see any increase in traffic, because the Bi-County Parkway is 15 miles away.”

Councilmember Marty Martinez said the council could not look only at the Bi-County portion of the corridor because the roads will all connect, and drivers will find them.

“They’re all going to connect eventually,” he said. “It is going to impact Leesburg and I have to be concerned about that.”

Councilwoman Kelly Burk said the chamber was putting business interests over those of residents.

“Economic development gets higher consideration than anything else – the environment, the community,” she said.

The council’s resolution included a list of projects it would prefer to see funded instead of the Bi-County Parkway, which the council requests undergo further environmental study.

Council members Kevin Wright and Tom Dunn voted against the resolution.

Opponents of the road held a conference call last week to offer an alternative plan that they said would keep 45,000 vehicles off of Loudoun’s roads. While those vehicles trips, the group acknowledged, would still exist somewhere in the region, they would have fewer impacts on the Manassas National Battlefield Park.

“The Bi-County Parkway makes conditions worse and doesn’t address some important needs,” said Stewart Schwartz, of the Coalition for Smarter Growth, one member of the group of opponents.

Opponents of the road have also argued that it primarily serves business needs, but forecasts show commuters would be the primary users, using the road to escape other congested routes. That would lengthen routes for commuters and prove a minimal benefit and other users crowd the new route, according to opponents.

Fin the full report with executive summary and appendices here.

The group offering the alternative vision for the parkway includes the Southern Environmental Law Center, the Coalition for Smarter Growth, the Piedmont Environmental Council, the National Trust for Historic Preservation, the National Parks Conservation Association.

Virginia Sec. of Transportation Sean Connaughton, who is the former chairman of the Prince William County Board of Supervisors, previously presented his case for the road in an editorial letter; read the letter here.

Howard said the disagreement would not harm the relationship between the town and chamber.

“We’re still friends,” he said. “The chamber’s going to continue to advocate for the town’s projects.”

The council’s resolution included a list of favored projects, including interchanges at the Route 15 Bypass and Edwards Road, Battlefield Parkway and Route 7 and Battlefield and the Leesburg Bypass. In addition, the resolution urges support for construction of Crosstrail Boulevard between Route 7 and Sycolin Road.

Photo courtesy of VDOT.