Battle lines are forming over the north-south transportation corridor in Northern Virginia. Backers say it would serve a growing population and stimulate economic development. Foes say the state has more urgent priorities for spending $1 billion or more.

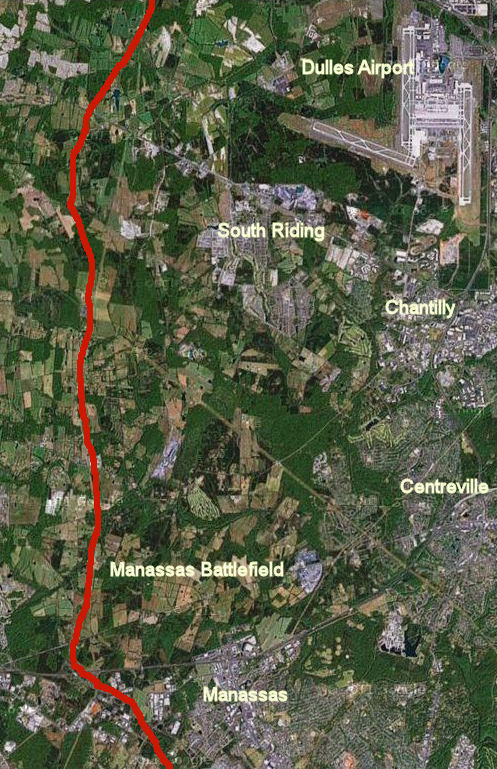

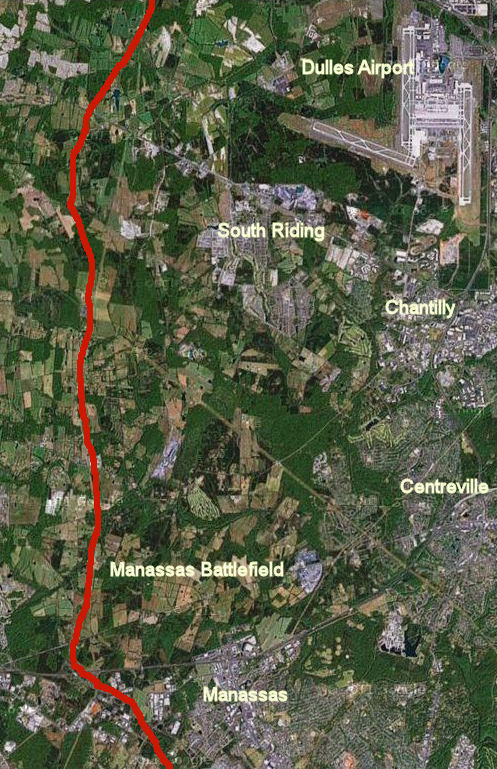

Red line shows approximate route of the North-South Corridor where it runs through the Manassas Battlefield and extensive farmland.

Northern Virginia, we hear over and over, is one of the most congested regions in the nation – perhaps the most congested. Even with new mega-projects coming on line like interstate express lanes and the rail-to-Dulles Metro service, the list of transportation needs seems endless. Most improvements under consideration are designed to ameliorate the traffic gridlock that grips the region now. But one particular cluster of projects zooming through the bureaucratic approval process is designed to address traffic congestion that is forecast to be a problem… in 2040.

In 2011, the Commonwealth Transportation Board (CTB) added the so-called North-South Corridor west of Dulles International Airport to its list of strategically important Corridors of Statewide Significance (CoSS), a designation that gives priority funding to projects within the corridor. It was the first time the CTB had added a new corridor not based upon an existing Interstate or rail line. Fast-tracking the project, the McDonnell administration has held public hearings and plans to present findings regarding a specific route and the cost to build a limited access highway this month.

Backers say Northern Virginia needs a north-south corridor – in particular, a limited access highway known in different configurations as the Tri-County Parkway or Bi-County Parkway — to accommodate the region’s fast-growing population and employment, and also to promote freight cargo-related economic development around Dulles International Airport.

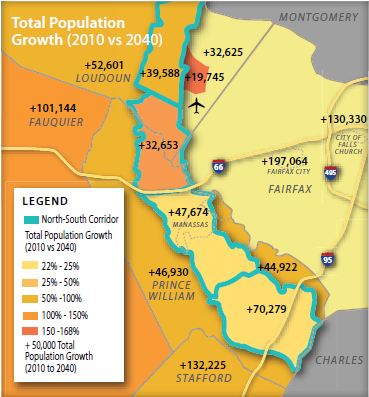

“If you look at the population projections of the [Metropolitan Washington Council of Governments] and the Commonwealth of Virginia, you see a major percentage of future growth in Northern Virginia does occur in this corridor and points west,” says Bob Chase, president of the Northern Virginia Transportation Alliance. “Loudoun and Prince William counties will add a couple hundred thousand people over the next 20 to 30 years.”

But skeptics describe the project as a wildly speculative endeavor that might enrich big landowners whose properties could be developed but otherwise do little to address Northern Virginia’s most pressing concerns. In particular, they say, Northern Virginia growth patterns in the 1990s and 2000s have zero predictive value for the future.

“The world has changed. Our population is older and is downsizing their homes. Empty nesters and younger workers want to live closer to jobs and transit, and in more urban places,” says Stewart Schwartz, executive director of the Coalition for Smarter Growth (CSG). “Moreover, the region has far more pressing needs serving existing population centers and addressing existing congestion. We need every dollar to fix existing commuter routes like I-66.”

Funding the north-south corridor, says Schwartz, would be “a misallocation of scarce resources.”

Only a year ago, the point seemed moot. Virginia was running out of state funds for new highway construction projects. But the north-south corridor controversy is sure to flare now that the General Assembly and Governor Bob McDonnell are close to approving a restructuring of transportation taxes that is expected to raise $800 million a year statewide for new transportation spending. Projects that had been pushed to the back shelves suddenly look fundable.

$2 Billion dollar project?

Northern Virginia’s major transportation arteries – Interstate 95, Interstate 66 and the Dulles Toll Road – all converge on the I-495 Capital Beltway or Washington, D.C., itself. Over the decades, population growth, job growth and development have followed those pathways out from the urban core. North-south arterials have been built to connect that growth, including the Fairfax County Parkway in the center of Fairfax County, and Rt. 28, farther west. The North-South corridor would represent a fourth such arterial but it would serve hypothetical future transportation demand, not a demand that exists at present.

Although the final plan has not yet been published, the North-South corridor likely will follow a path something like this:

- Apexct its southern terminus the highway will start at Interstate 95 in Prince William County. It will follow the existing Rt. 234, which becomes a partially limited access highway west of Manassas.

- The highway will proceed north across I-66 along the western boundary of the Manassas Battlefield and run parallel to Pageland Lane through miles of farmland, in areas zoned for low density — the so-called Tri-County Parkway.

- The highway will incorporate Loudoun’s expansion of Northstar Boulevard, crossing another stretch of undeveloped land, where it will connect to Belmont Ridge Road until it reaches the northern terminus at Rt. 7.

Because corridors of statewide significance are designated multimodal corridors, not just highways, the north-south corridor plan could include other components such as tolled express lanes and, in theory, Bus Rapid Transit, although there is unlikely to be much demand for mass transit in a rural area far from major job centers. Also, the McDonnell administration is studying the idea of linking the proposed highway to the western approaches of Dulles airport and upgrading Rt. 606, which runs along the western edge of the airport. These improvements would open property on the west side of the airport for commercial development.

Smart growth groups like the Coalition for Smarter Growth and the Piedmont Environmental Council view the north-south corridor as the same as an Outer Beltway proposal that belly-flopped more than a decade ago, with the main difference being that the McDonnell administration seems willing to build it piece by piece rather than all at once. The original plan for the Outer Beltway was to continue north, bridging the Potomac River and hooking up with a major Maryland arterial, opening vast tracts of relatively inaccessible land for new subdivisions and shopping centers. Maryland officials have made it clear that they have no interest in such a collaboration but the Virginia Department of Transportation is footing the bill in a separate study to examine the feasibility of building another Potomac crossing at an unspecified location.

The Office of Intermodal Planning and Investment (OIPI) is scheduled to present its recommendations to the CTB regarding the routing and corridor improvements, says Dironna Belton, OIPI policy and program manager. The OIPI will not make its cost estimates available until then.

Schwartz with the CSG guesstimates that the north-south corridor would cost a minimum of nearly $1 billion — figure $19 million per mile for 50 miles — only a small portion of which could be paid for by tolls. Some of the highway would follow the existing Rt. 234, he says, but construction work on an operating road is very expensive. Throw in some interchanges and the cost of connecting the highway to Dulles airport, he says, and the project could approach $2 billion.

Growth Projections

The argument for a north-south corridor is based upon the proposition that jobs and population growth will continue booming on the western edge of the Washington metropolitan region. That case is buttressed by forecasts made by the Weldon Cooper Center for Public Service’s Demographics & Workforce Group, which serve as the basis for state and local government planning purposes.

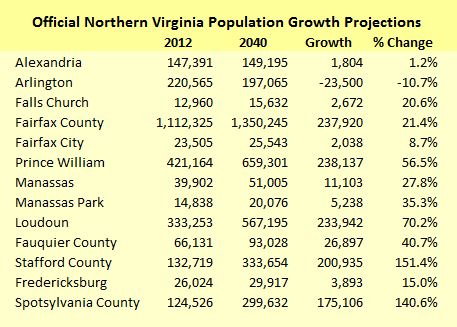

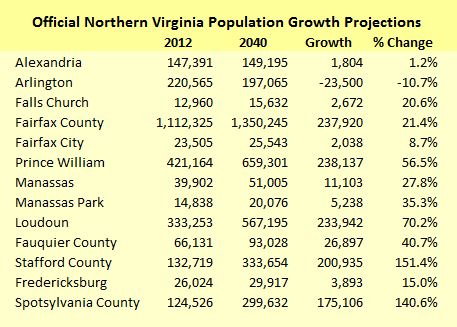

Here are the Weldon Cooper projections for the year 2040, listing jurisdictions in rough order of their proximity to the Washington urban core.

According to the Weldon Cooper projections, jurisdictions in the urban core like Arlington and Alexandria will see no growth – or actually shrink. Following the radius out from the core, Fairfax County will continue to see substantial growth in absolute numbers but only moderate growth as a percentage of its already-large population. The bulk of the population growth will occur in outer-ring counties, especially Loudoun and Prince William but also, traveling down Interstate 95, Stafford and Spotsylvania.

In just Loudoun and Prince William counties and Manassas, the jurisdictions directly served by the north-south corridor, the population is expected to grow by nearly 500,000 by 2040.

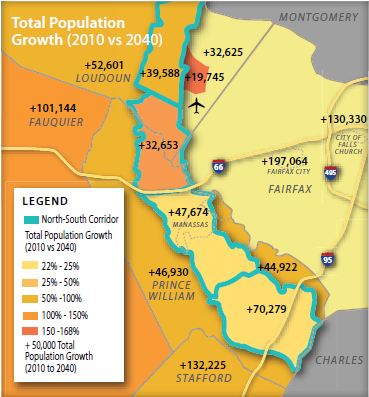

In its study of the north-south corridor, the McDonnell administration has embraced the forecast of booming exurban growth. “Nearly 700,000 jobs, 800,000 people, and 300,000 new households are expected to join [Northern Virginia] over this 30-year timeframe,” states an OIPI newsletter. “Much of this future growth is expected to occur within Loudoun and Prince William Counties. Larger portions of the new employment and population growth are expected within the North-South corridor area.”

According to maps published in the OIPI newsletter, population in the corridor study area itself will increase by 190,000 and jobs by 127,000. Population in areas immediately to the west will grow by 230,000 more.

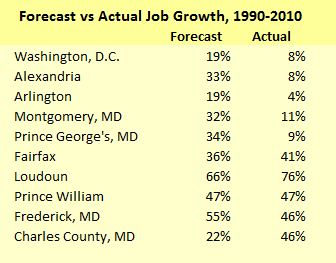

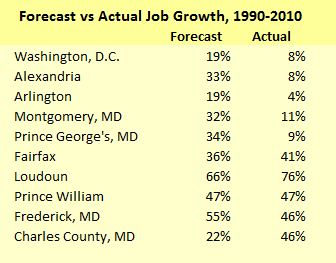

Chase with the Northern Virginia Transportation Alliance argues that the growth projections actually might be conservative. In a recent email, he distributed a chart, based upon National Capital Region Transportation Planning Board data, comparing a 1990-to-2010 job-growth forecast made for the Washington region with actual performance. Urban-core jurisdictions like Washington, Alexandria and Arlington under-performed the forecast by a wide margin while outer jurisdictions tended to out-perform the forecast. “These trends are expected to continue for decades to come,” he wrote.

In the battle over a proposed outer beltway a decade ago, which would have run more or less the same route, the Piedmont Environmental Council had warned that building the beltway would generate a population explosion, says Chase. “We didn’t build the corridor but the people came anyway.”

The idea that building roads causes population growth to occur that would not otherwise is wrong, Chase says, particularly in places like Northern Virginia with a strong economy and people moving in from all around the country.

Creating a north-south corridor makes sense, he says. As he wrote in the email cited above: “Most of the region’s workforce lives outside the Beltway and employers are moving closer to their workers. Moving jobs closer to where people live is more efficient than moving people (longer distances) to jobs. It reduces commutes and creates a better balanced, stronger regional economy.”

Inflection Point

A big problem with the Weldon Cooper population projections and all the forecasts based upon them is that they extrapolate past trends into the future. There is reason to question whether Northern Virginia can replicate the population and employment growth of the go-go 2000s during the austere 2010s.

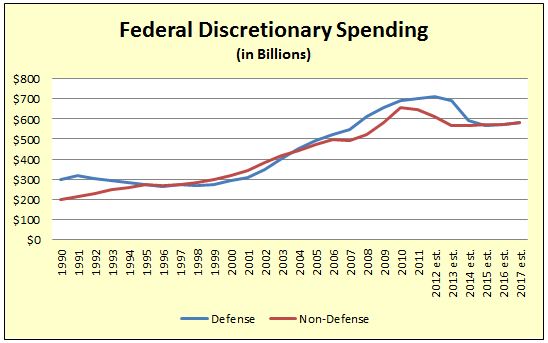

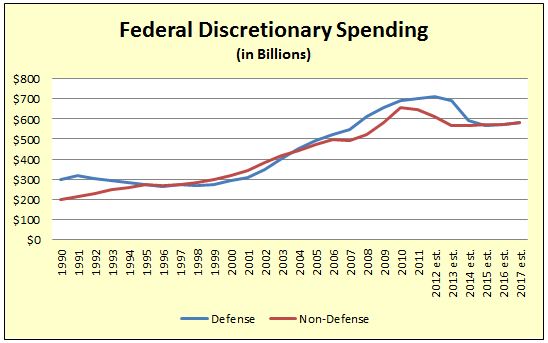

The terrorist attack on 9/11/2001 precipitated a decade-long growth in spending on defense, intelligence and homeland security, with much of the money going to federal agencies and contractors in Northern Virginia. With Washington adither over unsustainable budget deficits, however, the main question today is by how much defense spending will shrink. Likewise, spending on discretionary (non-entitlement) domestic spending is expected to level off, according to the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) data show below. While federal spending is not likely to collapse any time soon, it won’t provide the jet fuel for Northern Virginia’s growth that it has in the past.

Not only is population and employment growth likely to slow, smart growth advocates contend that the pattern of that diminished growth is shifting dramatically away from the peripheral counties of the Washington MSA back toward the urban core.

Many urban economists believe that the forces impelling metropolitan growth to green-fields on the periphery have petered out or even reversed themselves. That doesn’t mean there won’t be any job or population growth in places like Loudoun and Prince William, but it does suggest that growth could fall far short of projections based on past trends.

Major economic and demographic shifts are transforming growth patterns across America. Most notably, the cost of automobile ownership is outstripping the rate of inflation and household incomes. Over the past decade (2003 to 2013), the Internal Revenue Service deduction for business travel, a good proxy for the cost of owning and operating a car, surged 57% to 56.5 cents per mile, far faster than the 26% increase in the consumer price index over the same period.

There is good reason to believe that the cost of ownership will continue to rise. Global supply and demand forces will continue to push the cost of gasoline higher. Interest rates, a critical factor for automobile financing, can hardly get any lower and likely will climb. Federal fuel economy standards will save on gasoline costs but increase the cost of purchasing cars — a 2012 study by the American Automobile Association indicated that 122,000 licensed drivers in Virginia, or 1.9%, would be priced out of the market. Meanwhile, automobiles are evolving into mobile communication and connectivity hubs that add tremendous functionality but also push up the price. While the cost of driving is increasing, incomes are stagnating for the bottom 80% of income earners. Assuming the laws of economics still hold, Americans will adapt to the higher cost of automobile ownership by driving less.

That economic trend dovetails with major demographic trends. Two-thirds of all households today consist of singles, childless couples, or empty-nesters, and that proportion will rise over the next 20 years, Christopher Leinberger , a real estate developer, Brookings Institution fellow and author of “The Option of Urbanism,” has argued. Those households don’t need a big suburban yard where Little Johnny can run and play. They prefer smaller accommodations that require less maintenance and offer a variety of transportation options. Indeed, Leinberger says, there is a huge housing surplus in what he terms the “drivable suburbs” and a pent-up demand for what he calls “walkable urbanism” where inhabitants can meet many of their daily needs by walking, biking or riding mass transit.

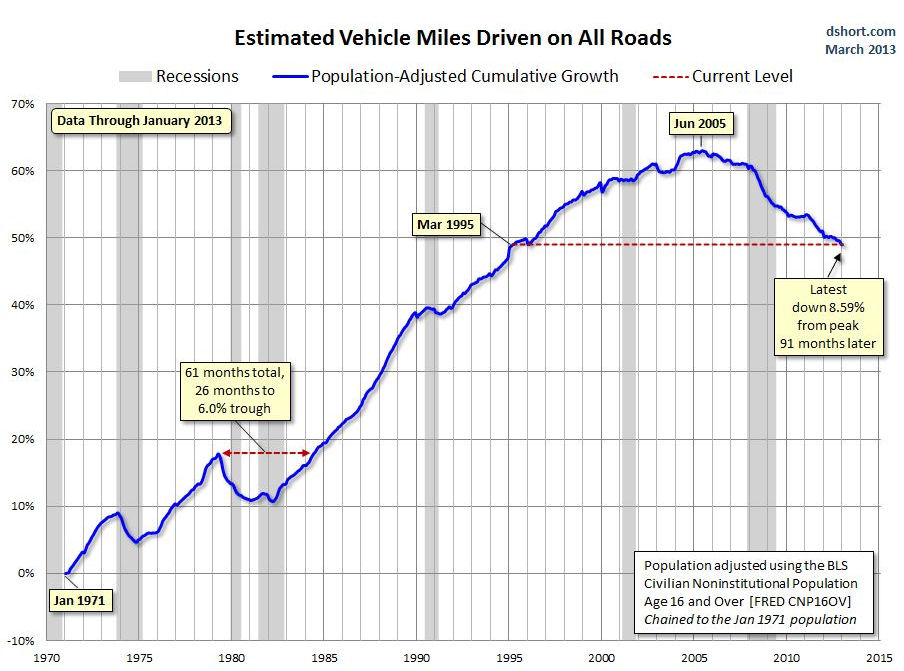

The evolving priorities are most evident among Millennials, the rising generation of 20- to 30-year-olds, who appear to be less enamored with automobiles than their parents were. In 2008, according to the Federal Highway Administration, only 46.3 percent of potential drivers 19 years old and younger had drivers’ licenses, compared to 64.4 percent in 1998. Similarly, drivers in their twenties drove 12 percent fewer miles in 2009 than twenty-somethings did in 1995. In big cities, many Millennials are abandoning the idea of car ownership and flocking to rental services like ZipCar and ride-sharing services like SideCar and Lyft.

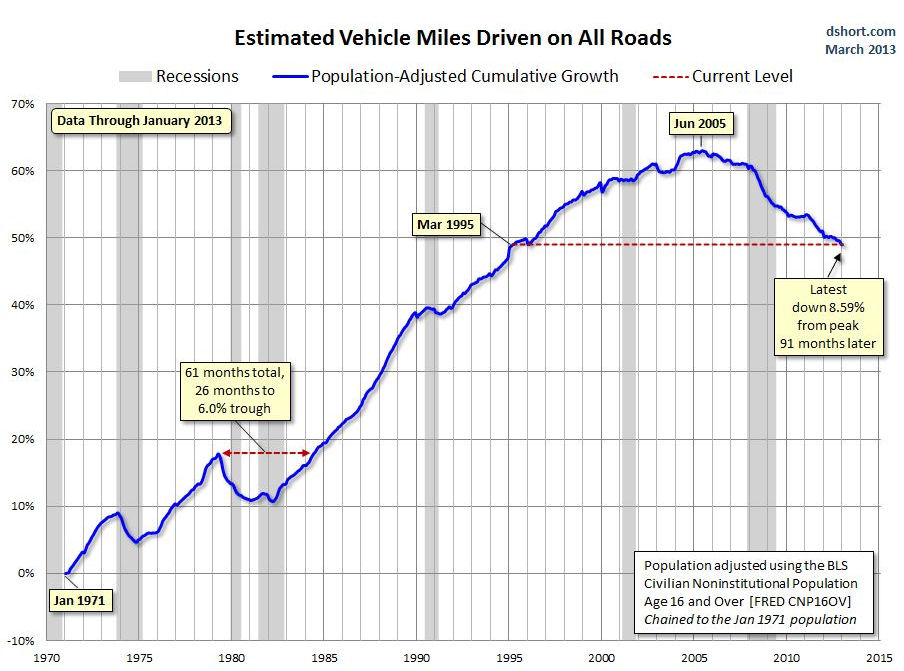

Consistent with these trends, the 12-month moving average of Vehicle Miles Traveled (VMT) plateaued in 2006 around 3 trillion miles, according to Federal Highway Administration data, and has dipped since then. Adjust for population growth, as seen in the chart below, and the decline is striking.

Graphic credit: Business Insider.

In the Washington region, developers are pouring billions of dollars into re-developing the District, close-in suburbs like Arlington, and even middle-band suburbs like Fairfax County. D.C.’s population increased by 30,000 over the previous 27 months, the Census Bureau reported in December 2012. Arlington planners, who count some 1,380 housing units under construction at present, project that 36,000 residents will move to their county by 2040 — diametrically opposite to Weldon Cooper’s prediction forecast that the jurisdiction will shed 23,500 people.

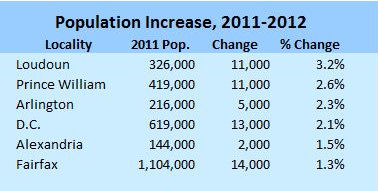

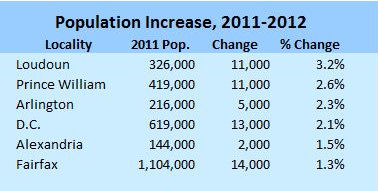

Here is the breakdown for population growth in 2012. At this point Loudoun and Prince William, which are working off a large inventory of houses and lots from the recession, are on pace with the Weldon Cooper projections. But Arlington and D.C. are coming on strong.

Meanwhile, Fairfax County is the sleeping giant. Nowhere is the shift in human settlement patterns more visible than at the 10 Metro stops planned for the Silver Line. Literally tens of millions of square feet of walkable, mixed-use development are planned for Metro stations along the Dulles Corridor. Fairfax County is undertaking a massive, multibillion-dollar transformation of Tysons from the prototypical auto-centric suburban office district into a pedestrian-friendly community. The addition of a strong residential component to Tysons alone could absorb between 20,000 and 40,000 new inhabitants by 2040.

Alternate investments

Given the pent-up demand for transit-oriented development and the massive resources committed to building it in Northern Virginia, diverting resources to the North-South corridor makes no sense, contends Morgan Butler, senior attorney for the Southern Environmental Law Center (SELC). Investing in the Silver Line so Tysons can be the center of growth while building a highway that facilitates sprawl are mutually contradictory aims, he says. Transit-oriented development represents the future, he says, and state and local authorities should focus limited resources on making it work.

Northern Virginia has many transportation needs that are urgent right now, much less three decades from now. Just one example: A recently issued Environmental Impact Statement found, for example, that nearly half of a 25-mile stretch of Interstate 66 outside the Capital Beltway operates at a Level of Service E or F (worse than free-flow conditions) during morning rush hour. Nearly two-thirds are deficient during the afternoon rush hour.

What kind of traffic relief could Northern Virginia buy with the $1 billion or more proposed for the Tri-County Parkway?

A coalition of smart-growth and conservation groups has published an alternative to the Tri-County Parkway that would not only protect Loudoun and Prince William farmland and steer traffic away from the Manassas Battlefield Park but ameliorate congestion that afflicts commuters here and now. States their “Updated Composite Alternative”:

Our alternative is designed to address the much greater need for east-west commuter movement and to provide for dispersed, local north-south movement for current and future traffic. Access to Dulles is provided by the completion of upgrades to Route 28 from I-66 north, improvements to the I-66 corridor, and upgrades to the Route 234/Route 28 connection and Route 28 on the east side of the Cities of Manassas and Manassas Park. The composite set of connections is designed to improve traffic movement throughout the area, benefitting more travelers and trip types than would the single large north-south highway proposal.

The document does not contain a cost estimate for the alternative projects, which includes mass transit and lots of local road fixes, so it’s not clear if the proposals constitute an apples-to-apples comparison with the proposed north-south corridor improvements. What is clear is that there is no lack of pressing projects competing for that $1-$2 billion.

The Air Cargo Push

Backers of a north-south corridor cite a second justification for the Bi-County Parkway: By improving access to Dulles International Airport, a highway would promote warehouse and logistics investment around Dulles Airport and even in Prince William County.

The Metropolitan Washington Airports Authority (MWAA) plans to develop 400 acres of airport property on Route 606, while Loudoun County is promoting 500 acres on the north-south corridor for cargo expansion, according to a December 2012 presentation made by Garrett Moore, then-district administrator for Northern Virginia. VDOT is conducting an environmental assessment for widening Rt. 606 on the western edge of Dulles’ property and a variety of other projects to improve western access to the airport.

“My gut tells me that Dulles in terms of cargo is about where we were with passengers in 1982. In those days, … there was very little passenger activity,” says Leo Schefer, president of the Washington Airports Task Force. But passenger service did take off. Dulles now is one of the busiest airports in the country and an economic engine of Northern Virginia. Schefer sees a parallel process underway with air freight. The established air cargo gateways are becoming more congested and more expensive to operate. The big logistics companies can cover their bets, he suggests, by establishing a presence at Dulles, which has enormous expansion potential and superior operating economics.

Schefer concedes that cargo-related development is not a sure thing. Unlike passenger service, in which airlines respond to rising traffic volume, “air cargo is more of an economic development exercise.” Northern Virginia economic developers need to persuade the big logistics companies to use Dulles as a strategic gateway where they can consolidate operations. That won’t be the easiest sell because the Washington region is not itself a huge market for air cargo. “We don’t produce much here besides paper,” he quips.

Northern Virginia is too expensive for the manufacturing sector, a major customer of air freight. However, Schefer sees that changing as new super high-tech manufacturing technologies are deployed and increasingly automated manufacturing processes rely upon fewer, more highly skilled employees. That kind of manufacturing could thrive in the region, he suggests, especially if manufacturers could avail themselves of superior air-freight access.

Be that as it may, Dulles has the real estate to accommodate large warehouses. “Logistics companies will want to see better truck connections,” Schefer says. “That’s where the north-south corridor comes in: A highway would provide superior access to markets to the west and south.”

Local economic developers view the situation similarly. “We view [the corridor] as an asset,” says Brent Heavner, marketing and research manager for the Prince William County Department of Economic Development. “One of the advantages of having better north-south transportation capacity is the market it opens up for industrial, warehouse and distribution users” in Prince William County, particularly the western county. “Right now those operations are at a disadvantage due to the circuitous route they have to move their freight to reach Dulles.”

A beefed-up air freight operation at Dulles might find itself competing with Richmond International Airport (RIC), which also has positioned itself as an air cargo handler. At this point, however, Dulles’ air-cargo ambitions have not made much of an impression on RIC. It’s not something airport management has studied, says Troy Bell, director of marketing and air service development. “We’re not anti-Dulles. But we have capacity and a very capable field.”

Schwartz remains skeptical of the economic-development argument. “Dulles is pushing its dreams on the rest of us. … They’ve justified the corridor by cargo growth at Dulles Airport. We think that’s a red herring. Air freight is a tiny percentage of total freight traffic.” While Dulles boosters have been promoting the north-south corridor, he adds, the air freight companies themselves have been conspicuously quiet.

There may be sufficient locally generated traffic demand to justify four-laning Rt. 606 on the west side of Dulles, a project that would cost $50 million, Schwartz says. But the Metropolitan Washington Airports Authority (MWAA) wants eight lanes and four interchanges, which could bump the project up to $300 million. “They’re asking for the taxpayer to pay for the expansion of Rt. 606. Why shouldn’t they pay for it?”

The way forward

In sum there are several imponderables the state needs to consider before putting money into the north-south corridor:

- Federal budget. Will the federal government deal with chronic deficits and a mounting national debt by cutting defense and discretionary spending, the lifeblood of the Washington metropolitan economy, and what impact would a spending slowdown have on population and job growth in Northern Virginia, particularly in the area served by the north-south corridor?

- End of sprawl. Do economic and demographic trends portend an historic shift in the pattern of growth and development in the Washington region, away from the growth frontier served by the north-south corridor and back toward walkable urbanism served by mass transit?

- Dulles air freight. Does Dulles air-freight traffic have a realistic shot at growth, and how significant is the economic impact of that growth?

- Alternative investments. How much will North-South corridor improvements cost, and how else could funds be deployed to mitigate congestion and create economic value?

Anyone can say anything. Anyone can make unsubstantiated claims. As Nassim Taleb, author of “The Black Swan” and “Antifragile” observed, however, players with “skin in the game” — with something to lose if they’re wrong — deserve to be taken more seriously than outside pundits and prognosticators.

One option for the commonwealth would be to solicit bids to build the Tri-City Parkway and other corridor improvements by means of a public-private partnership, in which private-sector partners would invest their own money. Private investors, unlike parties with a political or ideological axe or something material to gain or lose, would have every incentive to develop realistic projections for the key drivers of traffic volume and toll revenue: population, employment and air-freight growth. If corridor improvements create sufficient economic value, it should be possible to pay for the project with toll road revenue. If the demand is lacking or takes too long to materialize, as happened to private investors in the Dulles Greenway, private players will pay the cost of their miscalculation with their own money — not the taxpayers’.

The McDonnell administration’s experience with the U.S. 460 project between Petersburg and Suffolk, designed to serve a projected increase in port-related traffic, is instructive. Soliciting bids from three construction consortia, the Office of Public Private Transportation Partnerships discovered that the private sector was willing to fund only a tiny portion of the project. Demand for the facility would be more uncertain and take longer to materialize than originally anticipated. In a controversial decision, the administration chose to commit more than $1 billion in public funds anyway in the hope that the highway would attract major industrial investment.

Soliciting public-private partnership proposals for the North-South Corridor could yield similarly useful information. How much of their own money would investors bet on the prospect of massive population and employment growth in eastern Loudoun and western Prince William? Investor willingness to fund the project would eliminate grounds for complaining that the project is diverting state funds from Northern Virginia’s other transportation needs. Similarly, the unwillingness of investors to put their own money into the project without a massive state subsidy would be a clear sign that the anticipated benefits are either too meager, too chancey or too slow to materialize to warrant investment at this time.

Images courtesy of Bacon’s Rebellion

Read the original article here >>